More on types, typeclasses and the foldable typeclass

Marty Stumpf

7 Apr 2022

•

4 min read

This is the third of a series of articles that illustrates functional programming (FP) concepts. As you go through these articles with code examples in Haskell (a very popular FP language), you gain the grounding for picking up any FP language quickly. Why should you care about FP? See this post.

In the last post, we learned about higher order functions, which dramatically increase one's expressive power. In this post, we'll learn more about types and typeclasses, and the foldable typeclass, which will help us learn folds, an advanced and important tool.

Typeclasses and polymorphism

Typeclasses are categories of types, and so the instances of a class are types (not values)! For the types to be in a typeclass, they have to have certain traits.

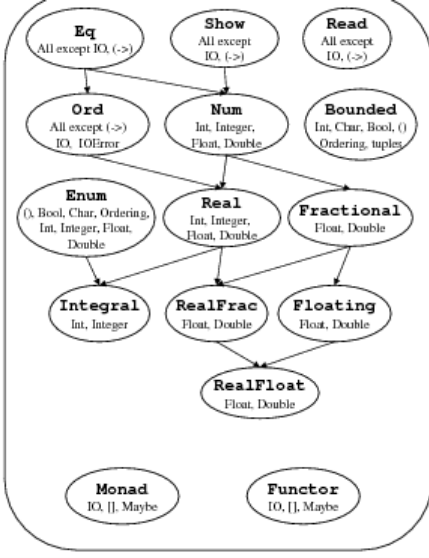

This graph shows the hierarchy of Haskell classes defined in the Prelude and the Prelude types that are instances of these classes:

As shown above, a typeclass typically contains more than one type. This is useful because it allows us to specify categories of types and still write polymorphic functions (functions that work on more than one type).

We've already seen the Ord and Num typeclasses in the last couple posts! Let's look at them in detail!

The ordering typeclass

In the first post, we saw the Ord (ordering) typeclass. It was a pre-requisite for the sorting algorithm to be applicable. If we have a type that is not ordered (e.g, a datatype of colours or shapes) then we cannot sort it. Therefore, when a type is in the Ord typeclass, it has a defined way of ordering the elements of that type.

The documentation shows that the Ord typeclass is a subclass of the Eq typeclass (everything in Ord is also in Eq):

class Eq a => Ord a where

In fact, as shown in the above graph, all except IO and (->) are subclasses of the Eq typeclass! This makes sense, if we don't know how to tell when things are the same, we cannot order them or do much else.

The documentation also specifies the associated methods of this typeclass:

compare :: a -> a -> Ordering

(<) :: a -> a -> Bool

(<=) :: a -> a -> Bool

(>) :: a -> a -> Bool

(>=) :: a -> a -> Bool

max :: a -> a -> a

min :: a -> a -> a

For a type to be in this typeclass, these methods are defined which means we can apply them to the elements of this type. E.g., from the graph above we know that all except a few types are in the Ord typeclass. So we can apply the function compare to instances of the Bool type!

compare takes two inputs, both of a type that is in the Ord typeclass, and returns the Ordering type. The Ordering type has three constructors (possible instances), GT (greater than), Eq (equal), and LT (less than). It may be unexpected but we can trust the documentation and run compare on Bool. Running compare in GHCi yields:

Prelude> compare True False

GT

Prelude> compare True True

EQ

Prelude> compare False True

LT

Similarly for the other functions:

Prelude> max True False

True

Prelude> (<) True False

False

The numeric typeclass

In the second post, we saw the Num (numeric) typeclass. It was a pre-requisite for our function g along with the Ord typeclass:

g :: (Ord a, Num a) => (t -> a) -> t -> Bool

g f y = f y > 100

Note that we call the function > in g. So we know that we must apply it to a type that is in the Ord typeclass. (As we see above that > is a method of the Ord typeclass. Because > takes two inputs of the same type and is applied to 100, a has to be an instance of the Num typeclass too because 100 is, as we can see from GHCi:

Prelude> :t 100

100 :: Num p => p

The Num typeclass includes instances such as Int, Integer, Float and Double. For a full list see the "instances" section in the documentation.

The foldable typeclass

Recursion schemes are powerful tool functional programmers should master. One of the most useful recursion schemes is fold. The Foldable typeclass has the methods foldr (the function for folding) and its variants.

Prelude> :t foldr

foldr :: Foldable t => (a -> b -> b) -> b -> t a -> b

The documentation also shows instances of the typeclass:

Foldable []

Foldable Maybe

Foldable (Either a)

Foldable ((,) a)

Foldable (Proxy *)

Foldable (Const m)

Note that the foldable typeclass instances are type constructors. They take a type to form a type. E.g., t a in the type signature of foldr. This means that t could be a list, or a Maybe, or (Either a) etc. These are the possible structures over a that we can fold. More on folds in the next post!

Understanding types and typeclasses deeply is important for every FPer and you've done it! As we progress we will see more types and typeclasses. Once you get familiar with them you'll have enough grounding to work with any type, and eventually create any type!

It's also very important to understand that folds can be used on many types. In the next post, however, we'll focus on folding a list, a common structure to fold over. I'm sure you'll be impressed by the power of folds, so stay tuned!

Marty Stumpf

Software engineer. Loves FP Haskell Coq Agda PLT. Always learning. Prior: Economist. Vegan, WOC in solidarity with POC.

See other articles by Marty

WorksHub

Jobs

Locations

Articles

Ground Floor, Verse Building, 18 Brunswick Place, London, N1 6DZ

108 E 16th Street, New York, NY 10003

Subscribe to our newsletter

Join over 111,000 others and get access to exclusive content, job opportunities and more!